I would like to start by asking you to consider an incorrect image. Imagine God, before He creates anything. He is not in Heaven, for He has not made it; He is not in space, for it does not yet exist. He is not anywhere, for the idea of place has yet to be created. So you cannot imagine anything outside of Him: you must simply imagine him, and you are bathed in him, swimming in the ocean of his being, an ocean with no shores and no surface, for all is submerged.

Next, imagine he takes the pencil that is His Word and draws a point of infinite smallness. This point is all of creation. He does not draw it anywhere, for, although place now exists, all the places are contained in that point: there is nowhere outside of it. And so the point, like your imaginative consciousness, is also submerged in God, yet other than God. God is the location and context for all of creation.

Now imagine that as God regards this infinitesimal reality, which is so small that it is almost nothing, His heart swells with love, and with a desire for union with it and its creatures. And yet, His heart is also broken because of sin. And so he decides to enter that creation. Imagine how far he has to travel if he starts from outside and travels in: About 45 billion light years to reach a galaxy called the Milky Way, then another 950,000 light years to arrive at the stellar system formed around the star Sol, and then another 1.8 light years (or about 9.3 trillion miles) to reach the third planet in that system, then another 9 miles or so to the surface, where the womb of a young virgin waits for Him.

Now this incredible journey, made up of numbers too big for our minds to comprehend, is an incorrect picture. It is incorrect it makes the assumption that the Word had to travel from outside the universe to get to Mary. But the universe is submerged in God: He is not outside of it, but is inside. God is not outside of place, He is in every place without being contained or constrained by any place. He is immediately present wherever you go. To enter the Blessed Virgin’s womb, He doesn’t have to go anywhere: He simply has to come to be there in a way that He was not before. If we have to think of this spatially, a quick side-step is more appropriate than the cosmic voyage I described.

Then why did I describe the cosmic voyage, if it is wrong? Because I want us to start with that mind-bending sense of distance, so that we can recognize how great the distance he has to traverse to become God-with-us is. For though he is not travelling through physical space, nevertheless to go from being eternal, omnipotent, infinite God to being a human baby is infinitely larger than the cosmic distance, or even than the very idea of physical distance. It is greater than the distance between something and nothing, greater than any other distance we know.

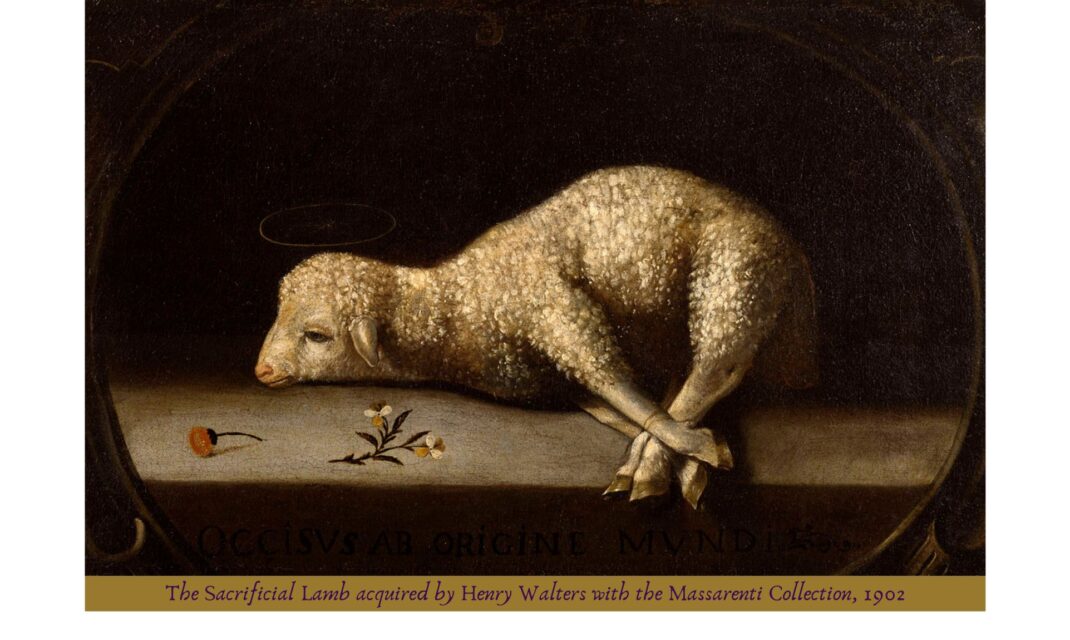

Why does He come all this way? Because He wants to become vulnerable. He wants to become vulnerable so that he may be killable. This is shocking, and is as offensive to many today as it was to the first hearers, instructed as they were by Greek philosophy and mythology in the deathlessness of the gods. But we must insist upon it, because it is preeminently fitting. The great problem to be solved was death; and so, since it was death with which God had to do, it was most fitting that He should meet it in a form that allowed Him to address it directly.

And so his destination was not the Virgin’s womb; that is just a necessary waypoint. His real goal is the cross, and, beyond it, the grave. The total negation of being that is Holy Saturday, whether it is the grave or Hell itself, is the furthest distance from God that one can go. Christ goes there in order to show that in the contradiction that is the meeting of Life and death, Life wins. He disproves once and for all every notion of duality that would make evil an equally ancient and potent enemy of the Good, and death of Life; for when Life stands in the very place where death has its throne, death must flee, and its power is broken.

And so the arrival of Christ is an event filled with sorrow, and his victory is what Sallust calls a “bloody and mournful victory.” [1] And yet it is also joyous, for it breaks the power of sorrow and mourning forever, dethroning them from their kingdoms. Christ comes to know with us how bitter is this Valley of Tears; but with his blood he fructifies the earth, sowing the seeds that will restore it to what it once was and ought always to have remained: a garden of delights.

It is dangerous business dealing with death on its own turf; but that is what heroes are for: to charge into danger and snatch safety for those who cannot save themselves. Satan mocks him at his seeming defeat: it is as if he says to Christ: “You have come a long way just to die.” But even in the midst of Gethsemane, even at the most extreme point of pain and sorrow, Christ can look the devil straight in the eye and reply: “Not just to die.” So we, too, should remember that Advent is about death, and that should make us sorrowful and cause us to bemoan our sins: for Advent is a penitential season. But we should also remember that death is only the furthest Christ went away from His center as God; it is not the end of his journey. For he retraces his steps, and in doing so, he exerts a powerful magnetic attraction that draws all willing creation back with him into the realms of glory. And so we grieve with hope: we pour out our sorrows so that we may prepare room in our hearts for the joy that is to come.

1 The Catilinarian Conspiracy, ch. 58.

If you enjoyed this article,

please consider Junius’s Advent companion resources below!

Junius Johnson is an independent scholar, teacher, musician, and writer. He is the executive director of Junius Johnson Academics, through which he offers innovative classes for both children and adults that aim to marry the sense of wonder with intellectual rigor. An avid devotee of story, he is especially drawn to fantasy, science fiction, and young adult novels. He performs professionally on the french horn and electric bass. He holds a BA from Oral Roberts University (English Lit), an MAR from Yale Divinity School (Historical Theology), and an MA, two MPhils, and a PhD (Philosophical Theology) from Yale University. He is the author of 5 books, including The Father of Lights: A Theology of Beauty. An engaging speaker and teacher, he is a frequent guest contributor to blogs and podcasts on faith and culture, and is a member of The Cultivating Project. Explore his work at juniusjohnson.com.