I

t is easy to think that Gabriel and the other angels knew what God was doing all along: that when the promise was made to Eve that her seed would crush the serpent’s head, they knew that it was a reference to Jesus, and that Jesus would be both God and man. All throughout the Old Testament promises, we feel, the angels see what the prophets do not, and rejoice in the great work that God is to do.

But what if they didn’t know? After all, 1 Peter 1:12 says that even the angels longed to look into the things pertaining to salvation. What if the prophecies were as dark to them as they were to us? Differently dark, perhaps: likely the angels would know that the promised eternal kingdom would not be the earthly nation of Israel, but a kingdom of a different sort, one in which we would be co-citizens with them. But between Abraham and the Kingdom of Heaven there is a vast distance of years, events, and possibilities: countless, perhaps even infinite, paths that a God of infinite creativity could traverse. And the angels, unlike us, are smart enough and holy enough to know that God’s imagination outstrips their own so greatly as to be utterly impenetrable unless he should choose to make his thoughts known. They would know not to try to out-guess God; or, at least, while they might delight in guessing and discussing what he might be about to do, they would know not to fall so in love with their own guesses that they feel he must do them.

If that is so, imagine the day Gabriel must have had when God summoned him to go to the Virgin Mary. “Go and tell her such and such,” the Lord says, and Gabriel perhaps experiences a moment of confusion. “That’s the messianic prophecy,” he thinks. “But that would mean…” His eyes slowly widen in comprehension. “You’re going to become one of them?” He asks. Then he remembers the rest of the prophecies, the bit about bloody sacrifice: now comprehension turns to horror. Or, if the angels cannot experience horror, to a kind of awe and wonder at the unthinkability of what God is setting in motion that shakes him to his core. “This is what it was all leading to? This was the plan? It’s wilder than our wildest guesses!”

You see, the infinite creativity and intelligence of God means that his thoughts are so high above ours (and those of the angels) that he can tell us exactly what he’s going to do, in such clear terms that when he has done it, it will seem impossible that the prophecies could have meant anything else, and yet allow that it still be utterly impossible to guess what he is going to do before he does it. It’s so easy to think that the Israelites and apostles were so stupid not to get what God was saying; but we wouldn’t have either. It was impossible to know until it happened. Not, perhaps, because it was simply unthinkable, but because even the prophecies do not point to only one possible fulfillment, and we cannot know which of the many, many ways of fulfilling them God would choose until the moment of choosing is past and the choice is made known.

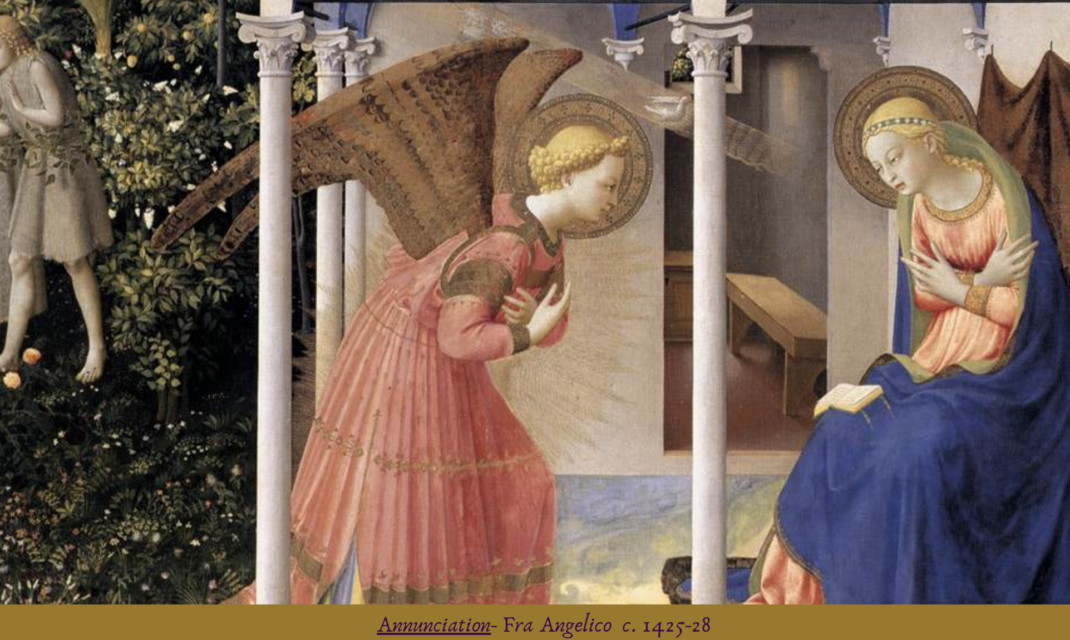

This is part of what makes Gabriel’s message impossible: that it is so far beyond his craziest guesses about what God would do. As he crossed those mind-bending distances we spoke of last time (though, even for him, they are likely more metaphysical than physical distances), his thoughts must have been racing with all the myriad implications. He replays every scripture in his head, and is blown away again and again by the vision of what they really mean, by the desperate wildness of the thing God will do to respond to evil, to break its power, and, ultimately, to destroy it forever. Perhaps some of the terrible fearsomeness of the angelic presence when they appear to humans is the fierce glow of their excitement and wonder at having learned, through the message they bring, new depths to the mystery of divine love.

But the other part of what makes his message impossible is what it will do to Mary. I think he loves her: I think he loves her because he is perfect in divine love, and this love includes and requires love of neighbor. Mary is his neighbor in the Kingdom of God, and he can see in her what God loves in her, can see how she is a unique and unrepeatable image of God (he sees it in you, too, and he loves you for it). And so his heart breaks for her, because he has got to tell her that she is going to be at ground zero of the greatest contradiction any creature has ever conceived, or could conceive: that God, the Lord of Life, would die.

This is a cosmic grief: it is the reality that all of creation has been lamenting and groaning over ever since that first act of disobedience, though it did not know it. We have to be very careful: we think all the world’s sorrows are for us, and that we are the ones to be pitied in this universal tragedy. But we are not: we are just the villains. It is God’s story, and it is his sorrow that has broken the universe. All of our sins are uniquely against him, as Psalm 51 teaches, and he is the one whose heart has been ripped open by our disobedience, disrespect, scorn, and rejection. The whole world groans for what was done to God.

But Gabriel sees, as he wings his way to her chamber, that all of it has to be placed on Mary. The death of God is the greatest of all griefs: it is every grief concentrated into one, it is the gathering up of all grief so that it can be borne in one moment, so that it can be borne in one life. We all have a share in it, and we are all of us bereaved by it, for we are his people, and the death of our Lord is also the death of our own hope. But it is Mary’s sorrow in a special way: no less than all of us is it the loss of her Lord, but it is also the loss of her beloved son. She alone of all of us will feel something of what God feels as the bereaved parent losing the light of his life. This is a hard saying, and Gabriel’s newly expanded heart must have been breaking in ways too comprehensive for us to even bear the thought of as he carried out his mission. All generations will call her blessed, but Gabriel knows better, knows that this will not be her experience, and perhaps cannot be until she is received into the Kingdom where all sorrows go to die.

If you enjoyed this article,

please consider Junius’s Advent companion resources below!

Junius Johnson is an independent scholar, teacher, musician, and writer. He is the executive director of Junius Johnson Academics, through which he offers innovative classes for both children and adults that aim to marry the sense of wonder with intellectual rigor. An avid devotee of story, he is especially drawn to fantasy, science fiction, and young adult novels. He performs professionally on the french horn and electric bass. He holds a BA from Oral Roberts University (English Lit), an MAR from Yale Divinity School (Historical Theology), and an MA, two MPhils, and a PhD (Philosophical Theology) from Yale University. He is the author of 5 books, including The Father of Lights: A Theology of Beauty. An engaging speaker and teacher, he is a frequent guest contributor to blogs and podcasts on faith and culture, and is a member of The Cultivating Project. Explore his work at juniusjohnson.com.