Over the course of each week during Lent...

Dr. Junius Johnson will bring us weekly reflections and guide us in discovering the practices and principles that amount to lifelong discipleship.

Repentance is the central purpose of Lent because sin is the central reality in our lives. As long as we fail to see this, as long as we think of sin as some side note to our being, as something we do rather than something we are, we are failing to really see the depths of our desperation and the wildness of the salvation offered to us. The saint truly aware of her sin is flabbergasted by the redemption in Christ, by the fact that reconciliation should be possible at all at any price, by the rank injustice of the fact that God would even want to be reconciled to her.

This is the great miracle of Christianity: not the death and resurrection of God, which both serve to ground the true miracle, but the forgiveness of sins. Without it, we could have no share in Christ’s resurrection.

But we cannot come to see this apart from repentance. I think I once thought that the awareness of the depth of one’s sin was the necessary condition for repentance.

Now it seems to me that repentance is the necessary condition for the vision of the depth of one’s sin.

The sting of conscience that is required to get repentance going is but the first shadow of the vision of our sin. This is in part because our sins do not leave us unchanged: they damage us, warping our vision and muddying our thinking and the longer we persist in ignoring our sin, or justifying it to ourselves, the more detached from reality our vision becomes. The ultimate end of that trajectory is an inability to see that one has acted poorly at all. Thus the sinners in Dante’s Inferno are constantly telling him that they are victims, that it’s all unfair, that there has been a miscarriage of justice. (Dante should know better: on the very gates of Hell there is the declaration: “Justice caused my high architect to move, / Divine omnipotence created me, / the highest wisdom, the primal love” [Inferno III.4-6].) We are kept from reaching the fullness of this position by the eternity in our hearts that witnesses to the fact that we are wrong. Thus, on the Last Day, each will confess his own crimes, and all our excuses and justifications will die stillborn in our mouths.

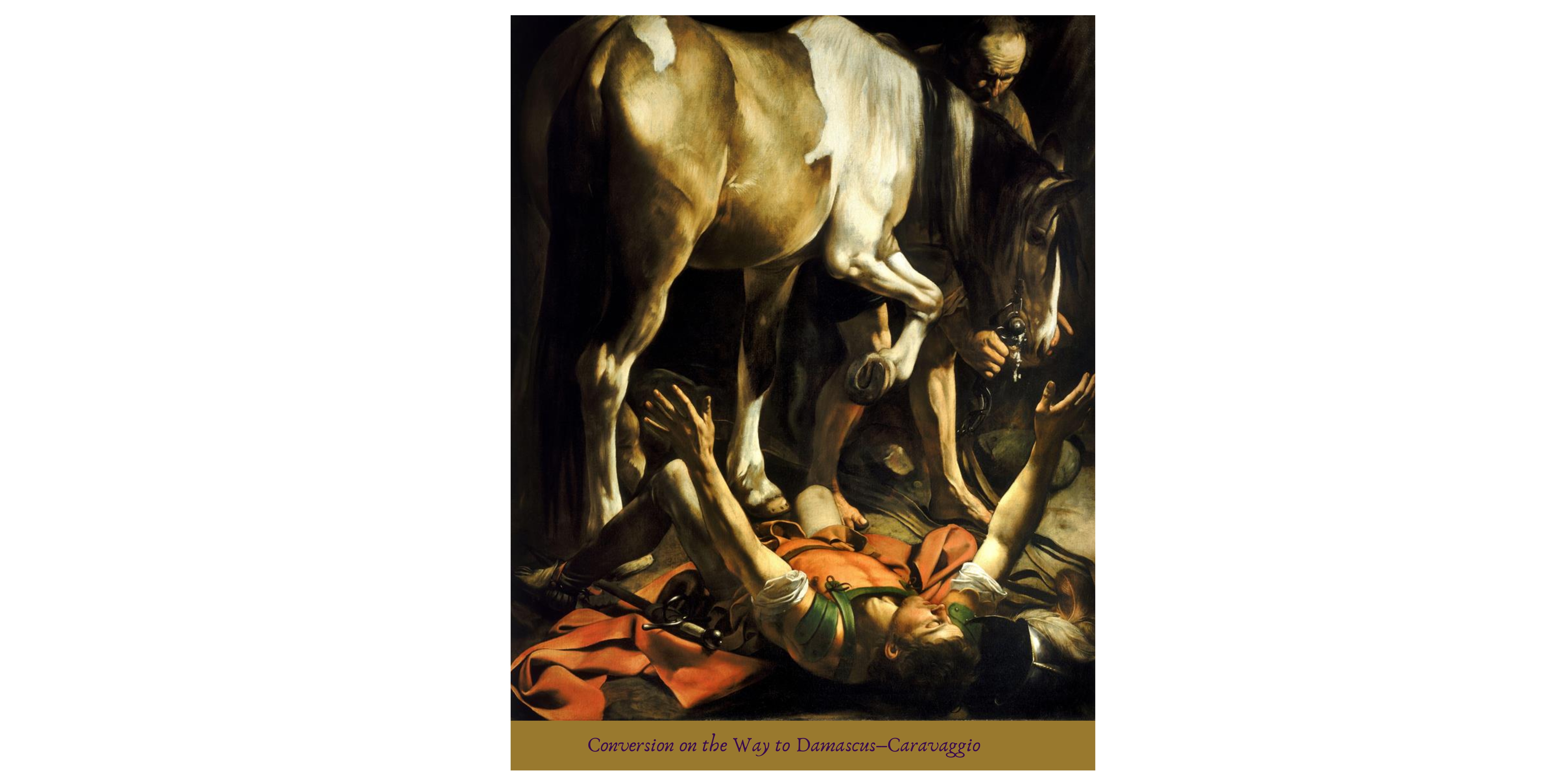

As one walks the path of repentance, one’s head begins to clear, and one’s vision is restored. Repentance is often described as a retreading of one’s steps; this peripeteia, or “reversal,” should also put us in mind of Aristotle’s claim in the Poetics that every good tragedy turns upon such a moment. The tragic reversal is the realization that recasts everything the character thinks he knows into a horrific light: you have in fact killed your father and married your mother; the delicious stew your wife served you is made from your children; MacDuff was from his mother’s womb untimely ripped. The Christian on the road to repentance also suffers such a reversal, when he comes to the place where vision has been clarified enough to begin to see for the first time what the sin really looks like. This is the vision that drives us wild, that casts us into the depths of despair: but it is not yet the full vision of our sin. As we walk further down the road of repentance, a road with no clear end, we see better and better, we come ever more to see the sin as God sees it. This is, for me, the worst part, because it means having to face the reality of just how deeply I have grieved the heart of God. This experience is inseparable from repentance, because it is the very work repentance has to do: to wrest oneself away from the sin, to refuse to be identified with it, to make enough space between yourself and the sin for there to be something for God to save.

“The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness.” (Mark 1:12, ESV)

As Jesus was driven into the wilderness, so we are driven to repentance. The Spirit hounds us and will give us no rest until we set foot on that road; and there is no rest on that road either, for repentance is not a place for resting. We must, with utmost urgency and all possible haste, return whence we came, return to the One from whom we came.

And yet, for all that we have to work to hold ourselves to the path of repentance, to daily refuse the temptation to begin to rationalize and justify (“Was it, after all, really so bad?” “Well, it wouldn’t have happened if so-and-so hadn’t done such-and-such…”) and continue to face the fact that, all external circumstances aside, we chose to wound the heart of God in just this way; for all of that, it never becomes possible to earn reconciliation, or to deserve forgiveness. The point of repentance is not to feel bad enough for long enough that God and others are justified in forgiving us: the point is to un-become the kind of person who would do the thing we are repenting of.

But this work would be infinite if not for divine intervention, because we cannot complete it.

We lack both the will and the power to be freed of our sin. We cannot be reconciled, both because we cannot fully repent and because we don’t really want to. For each step we take on the path of repentance, we need the empowering of the Holy Spirit.

But Christ on the cross sets the end point to all repentance: it is not our works of repentance, but Christ’s work of sacrifice that saves us. The road of repentance ends at the foot of the cross: when we have come there, we can let go and trust in his accomplished work.

Repentance and penance bring us into tune with his salvation and guide us under the umbrella of its gracious embrace. For this reason, all penance ends on Good Friday, and the feast of Easter is a feast of accomplished reconciliation.

I will add just one more thing here, as if it were an afterthought, when in fact it is integral: the clearest condition of our forgiveness in the Gospels is not our desire to be forgiven, but our willingness to offer others the same forgiveness we have received. The parable of the unforgiving servant (Matthew 18:21-35) and even the Lord’s prayer (“forgive us our trespasses just to the extent that we forgive those who trespass against us,” the original Greek says) leave us no room for the luxury of unforgiveness. When Peter asks how often we should forgive our brother, he is asking what the limits of forgiveness are. It is instructive and convicting that Jesus doesn’t say as long as he is really sorry, or accepts responsibility for his actions, or promises to act differently, or actually acts differently. He says, in essence, “as many times as you have opportunities to.”

Because we seek to be forgiven during Lent, we should be especially zealous to offer forgiveness to those who need it. Christ himself urges us to be reconciled to one another, and longs for us to experience a radical unity, one that is in some mysterious way a shadow of the trinitarian unity. Lent is a season for horizontal as well as vertical healing.