Over the course of each week during Lent, Dr. Junius Johnson will bring us weekly reflections and guide us in discovering the practices and principles that amount to lifelong discipleship.

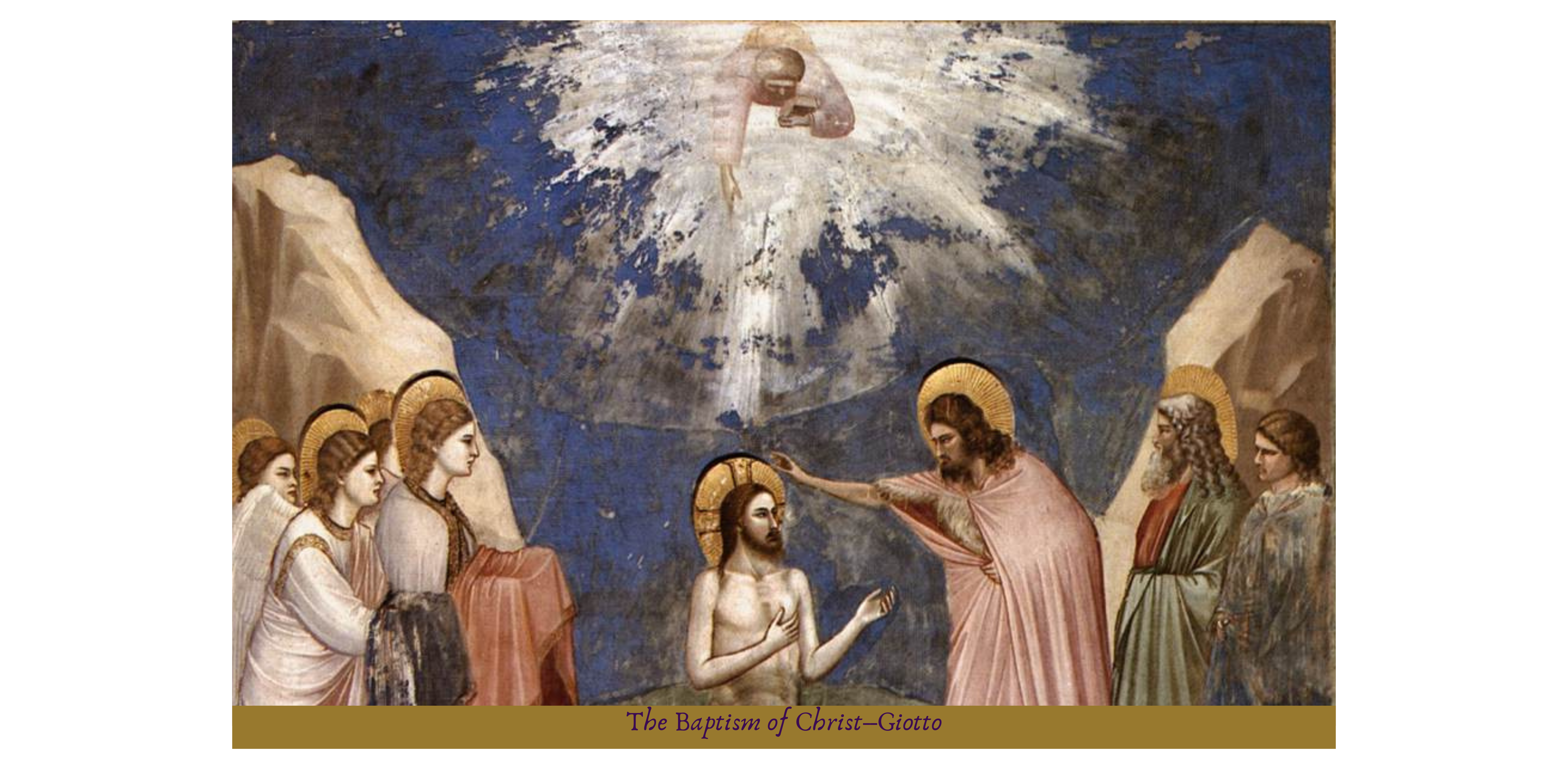

And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased.’ The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. (Mark 1:11-12, ESV)

What a startling juxtaposition! It is difficult not to read the immediacy with which Mark’s narrative moves from “I love you” to “get thee to temptation” as a “therefore:” because I love you and am well pleased with you, you must go into temptation. Mark’s choice of verb here is also interesting: Matthew and Luke say that the Spirit led him, but Mark says that the Spirit drove him. He is left no choice: he is hounded by grace, but hounded into temptation.

Or is he? He doesn’t go into the wilderness to be tempted, he goes into the wilderness to pray, to fast, and to purify himself. It is a time of dedication; the temptation is just the inevitable consequence of intentional dedication. He is led to the place of temptation, but not in order that he might be tempted. The Father knows that the temptation will come, but he aims at something else in driving him to that place through the Spirit. This has really important consequences for our own times of being driven out.

Traditionally, Lent was a time when catechumens would prepare to receive Baptism on Holy Saturday. In the Middle Ages, it was also used as a time of preparation for knighthood, which would be conferred on Easter Sunday: the knight would fast and pray throughout this season so that his soul was well prepared for the vow he was about to undertake. One to be ordained to the priesthood would likewise use this season as a time of preparation.

Why such a long preparation? Because in each case, the preparation culminated in a holy vow taken before the Lord, and such things are not to be taken lightly. It was a big deal to take on knighthood, because it was a calling that would consume all aspects of your life: you are choosing to serve your honor, which consists in the helping of others and the dutiful rendering of service to your Lord. It meant binding your good to the promotion of the good of others. It was a big deal to be made a priest, to have your entire life given over to the service of God’s people and to bearing their burdens. Baptism was the biggest deal of all: you were becoming a slave of the Lord, you were being inducted into spiritual Israel, which means that now you must struggle with the Lord (the etymological meaning of Israel, Genesis 32:28). And it is no mean thing to struggle with God. Although Jacob is said to have prevailed, he walks away from that encounter with a dislocated hip and would likely limp for the rest of his days.

What can this mean? It means that we must take the language of Scripture seriously when it says that we must die to self. This is no mere metaphor, and it is certainly no hyperbole. The death to self is not less literal than what we normally mean by death, the death of the body; it is more literal, because who we are is even more bound up in our souls than in our bodies (though it is bound up with our bodies, too).

The spiritual death to self required to enter into the service of the Lord is the reality of which bodily death is the shadow. And if we tremble so much before the shadow, who can stand to face the dragon who casts it? Well might we take a full season of preparation to come to that encounter.

This is all a powerful and sobering reminder for the one preparing for Baptism, or commissioning to the ministry, but that doesn’t describe most of us at Lent. But their trials are not for them alone. In the ancient church, the community would share in the journey of those preparing for Baptism. They would be obvious in the worship, likely sitting together, and possibly even dressed differently. They were not allowed to be present when the Lord’s Supper was celebrated, and so at that point in the service they would stand up to leave. This might cause conflicting feelings in the faithful who remained: joy that they were on the journey to being admitted to the mystery, but sorrow that they were not yet able to taste the goodness of the Lord that waited on the altar. Their presence was a continual reminder that there is a door to the Church, and that one must come in by that door or not at all.

Thus, even for the believer who is not journeying towards Baptism, or confirmation, or rededication, or being set apart for ministry, Lent can serve as a season of remembering one’s Baptism and renewing the fundamental commitments of discipleship (whether these be expressed as formal baptismal vows or not). Initiation was never directionless: the initiation of the knight aimed at the bestowal of his sword, which he would ever after hold in trust from his lord and only use in ways consistent with his duties to his lord (principally, protecting the lord and his people); ordination aimed at the total and complete change of the life of the believer from one who is served to one who serves, from one who receives to one who dispenses. And Baptism aimed, in the ancient church, at the regular encounter with the risen Lord through the bread of the presence, the very body that either lay on the altar or was commemorated there.

So, we are driven out into the wilderness by the Spirit, not to be tempted, but to be made ready to receive the risen Lord on Easter.

A sinful people that remains at peace with their sin is not ready to greet the resurrected Lord with joy. Such a people can only greet him with dread, because his coming means the end to their kingdoms, the end to their joys, the end to their callousness.

A sinful people can only see the risen Lord as Herod saw the newborn Christ: as a threat. To rejoice when it is announced to us that the Lord is risen on Easter morning, we have to be made into a different sort of people: one that hates its sin, that has turned away from it, that has worn out its eyes weeping over it. To such ones is the risen Lord the Savior.

But, as with the Lord, so it will be with us. The wilderness is a place of temptation because Satan does not want to see us receive the Lord with joy. He would have companions in his misery, and he will do all he can to secure them. And so know that your efforts will be resisted, that you will know temptation, and that it will be bitterly difficult to resist. The wilderness is a place of temptation; but that means that it is also the crucible of faithfulness.