Content taken from The Evangelical Imagination by Karen Swallow Prior ©2023, “Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group. Used by permission.

What is it about so much contemporary “Christian” art that makes it so bad so often? Even the complaints have become cliché.

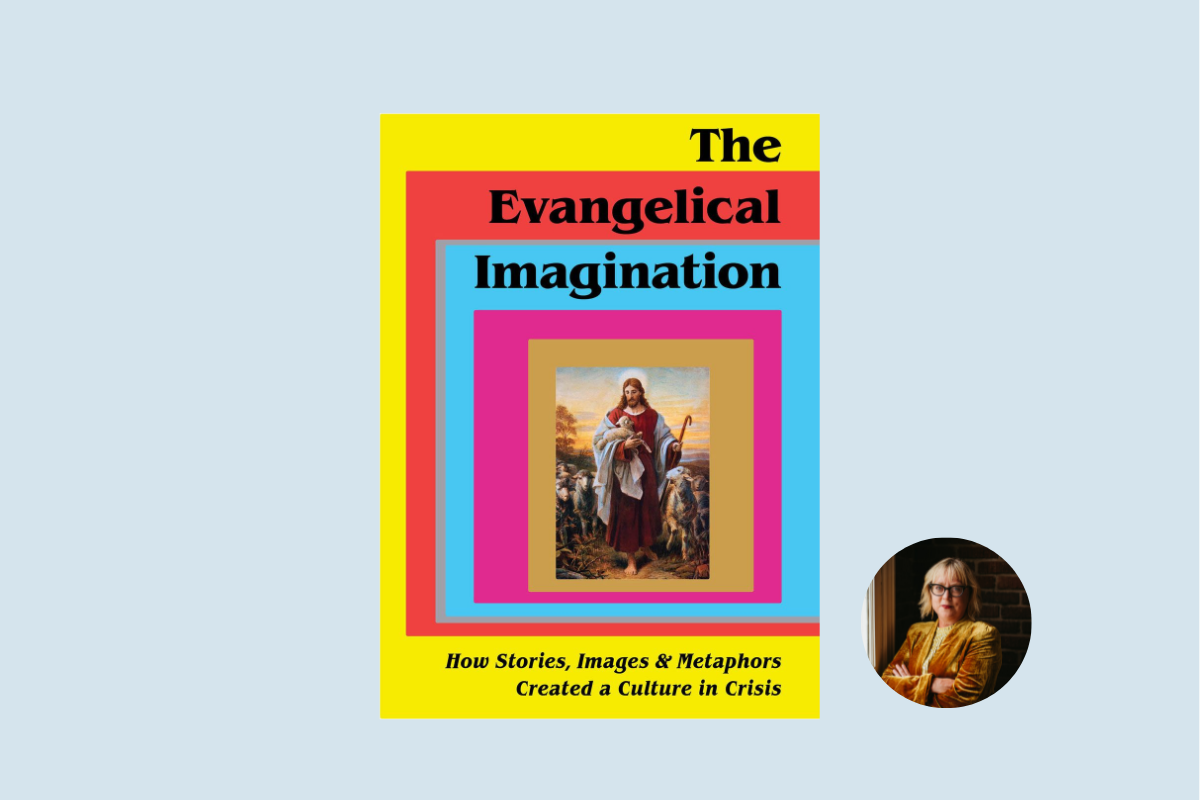

To be sure, there are many Christian writers and artists today who strive to defy this stereotype and succeed. Nevertheless, Christian art has a problem. It’s easy to think this problem began with the cheesy evangelical movies and Christian rock of the 1980s and ’90s. But the fact is that bad evangelical art has a long and interesting history. Of course, bad art can be bad for any number of reasons (such as lack of imagination, execution, or skill). But what tends to make evangelical Christian art bad is its sentimentalism.

The word “sentimental” is most often used in a context in which an object is cherished not for its monetary worth but for the feelings it evokes, usually emotions associated with the memories or relationships the item represents. In fact, the word “sentiment” is nearly synonymous with feelings or thoughts. (Pedants take note: because to have sentiments about something means to have thoughts or feelings about it, there is no need to be critical or disapproving when people say, “I feel . . .” instead of “I think . . .” The meaning is essentially the same.)

Sentimentality itself isn’t necessarily bad. But sentimentalism is an emotional response in excess of what the situation demands; it’s an indulgence in emotion for its own sake. It is emotion that is unearned. As Victorian critic Leslie Stephen puts it, sentimentalism is “the name of the mood in which we make a luxury of grief, and regard sympathetic emotion as an end rather than a means.” To be wary of sentimentalism is by no means to reject feelings but rather is to recognize when emotion surpasses what is warranted. Like having candy for dinner every night, sentimentalism—meaning a way of life or worldview—can cause harm when it is not recognized as the indulgence that it is and then becomes a regular habit of life or a way of conceiving of the world.

Sentimentalism is an emotional response in excess of what the situation demands; it’s an indulgence in emotion for its own sake.

Excessive emotion can develop from within ourselves, arising from our own individual propensities or personalities. But emotionalism can also be evoked by external manipulation. This is what sentimental art does: it attempts artificially to create feelings that exceed what the situation warrants.

Television commercials using sweet puppies or cute babies to wring tears from our eyes in hopes of selling a certain brand of beer or phone service are obvious examples of the easily exploitative powers of sentimentality.

If the purpose of art is to recreate human experience, the purpose of sentimental art is to recreate emotional experience. This can be harmless—such as when a souvenir from a vacation brings back warm memories of a cherished trip. But sentimentalism can do harm when emotions are evoked apart from or subordinate to other aspects of the human experience (such as intellectual, spiritual, or physical experience) and thus to the totality of what is real. Whether portraying things in terms overly sweet or overly sad, or whether interpreting people (who are complex) as one-dimensional heroes or villains, sentimentality smooths over the rough edges of reality and glosses over hard questions so as to tie things up neatly in a bow. Even glorified violence and prettified barbarity are forms of sentimentality because the emotions they evoke are distorted and thus detract from the ability of art to convey truth. There is a reason the ancients used the word “obscene” (which literally means “against the scene”) for those things not fit to be portrayed on the stage.

Sentimentality smooths over the rough edges of reality and glosses over hard questions so as to tie things up neatly in a bow.

In the classical tradition, truth, goodness, and beauty are understood to be three transcendental qualities or universal realities that originate in and lead to the eternal and divine. The Christian tradition emphasizes the trinitarian relationship of these transcendent realities, each of which finds its source in and reflects God (as reflected by Augustine’s address to beauty quoted in chap. 2). Beauty is the quality that makes truth and goodness manifest.

It is easy to confuse the beautiful with the sentimental because in some ways both are aesthetic experiences. The root meaning of “emotion” is stirring, agitation, or movement, which later came to mean “feelings.” At the most fundamental level, an aesthetic experience is an affective experience, one that moves us. To be moved by something is to experience a bodily response, such as a quickened heartbeat, widened eyes, gathering tears, a gasp, a nod, or a smile. Sentimental art can move us or evoke emotion, just as true beauty does. But not all movements are equal.

Consider this famous passage from Milan Kundera’s novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which points to the difference. Kundera is defining “kitsch,” which is cheap, derivative, sentimental art. Kitsch comes in many forms, including amusement park souvenirs, garden gnomes, knickknacks, Hobby Lobby wall decor, Lifetime movies, and so on. Kundera explains kitsch this way: Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass!

Kitsch, like sentimentalism, indulges emotion for the sake of the emotion itself. And as Kundera points out, that second emotion is self-aware and self-satisfied. Again, emotions are not bad. They are good. They are essential to our humanity. But divorced from their proper purpose of rightly driving our thoughts and actions, sentimentality is akin to pornography, as Flannery O’Connor memorably puts it in Mystery and Manners.

For both sentimentality and pornography sever the experience (emotional in the first case, sexual in the latter) from its meaning and purpose.

In reality, you can’t have beauty apart from truth. Beauty apart from truth and goodness is mere sentimentality.