Over the course of each week during Lent, Dr. Junius Johnson will bring us weekly reflections and guide us in discovering the practices and principles that amount to lifelong discipleship.

Jesus prayed. That is astounding. It is astounding because of who he was (and is): he was God himself, eternal, there before the foundation of the world, the architect of the foundation of the world. He knew God’s purposes from all eternity, for they were his purposes. He knew them during his human life, as he himself makes clear on many occasions. Why would this person need to pray?

But the reason why he prays is also because of who he was (and is): he is not only God, not any more, not since Mary uttered the most important “Let it be” of human history. Now he is also human, and as human, prayer is appropriate. So yes, it is astounding that he prays, but the mystery of his praying is the mystery of the personal union of divinity and humanity in the one Savior.

And yet he does not pray for many of the reasons that we pray, and that allows us to see what the essence of prayer really is.

He does not pray in order to find out what God’s will is for his life, for he knows it, and sees it spelled out in Scripture in a way none of us can, because while every Scripture speaks to us, every Scripture is about him. He does not pray for the forgiveness of his sins, because he has none. In fact, lacking sin, he also lacks that interruption of relationship with God that sin brings about. He and the Father are one, not just in their divinity, which grounds an eternal oneness that is the very meaning of the word “one;” they are also one in his humanity, in the sense of union with God that awaits all the saints at the consummation of all things. So it doesn’t seem that he would need to pray to draw near to God either.

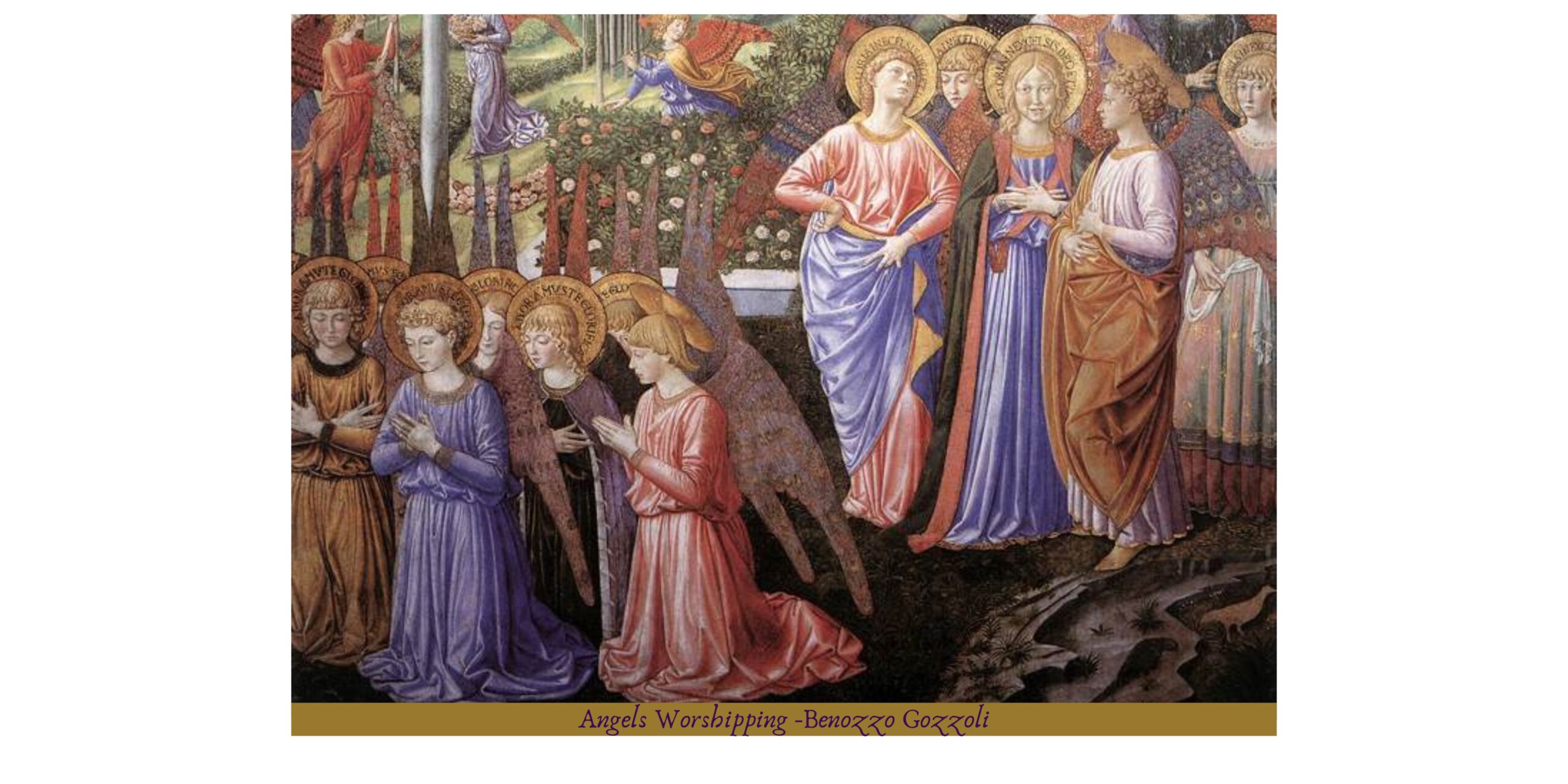

But if we look at Jesus’ prayers, what we see is that he is working on his relationship. He prays before all the big moments of his life, most notably in Gethsemane. And this is not merely “to fulfill all righteousness,” which I confess I usually think means “to keep up appearances.” He is so ardent in those prayers that he is sweating blood. I’ve never been that worked up about anything in my life. And what is he praying for? “Not my will, but your will be done.” He is working in prayer to bring his will into line with the divine will. Prayer for Jesus meant tuning his heart to the heart of God.

Turning back to Lent: originally, fasting meant skipping meals. It therefore created time in your day that you wouldn’t normally have, and that time was devoted to prayer. In this way fasting and praying weren’t two different things, they were two aspects of the same thing. We fill up the spaces of fasting with prayer. I try to emulate this as best I can: whenever I want the thing I’m fasting from, I use it as an occasion for prayer. But in general, because my fast is not from meals, it doesn’t create more time in my schedule. Thus, to take on prayer as a spiritual discipline in Lent means making time for prayer.

In fact, I would say this was always the spiritual meaning of prayer as a Lenten discipline. For Christians are called to pray at all times: indeed, to pray without ceasing. Prayer can only be a Lenten discipline if it is something added on top of what we already do, if it is additional time spent in prayer. In this sense, if the allegorical meaning of fasting is setting aside something we normally do (of which eating is just one option), then the allegorical meaning of prayer as a Lenten discipline is that we take on something we don’t usually do. And so prayer as a Lenten discipline could be taking on a discipline such as Bible reading or more intentional Sabbath-keeping.

The purpose of prayer is to attune our souls to the will and grace of God.

Lenten prayer aims to reorder our time and our thought-space around the promises, deeds, and being of God.

Structure is really helpful here, because the rigors of Lent will make you want to cut corners. Work through a devotional, or pray through a book of the Bible, or set a regular time every day to pray with your spouse, family, or friends. Jesus went into the desert to have uninterrupted prayer time: what would it look like for us to create that kind of protected space?

And we have to remember that it is not impersonal, and it is not a monologue. Prayer is a date with God. On a good date, you listen as much as you talk, because you want to know more about this person, because you hang on their every word. But you must speak, too, because just as the good date cannot be all about you, so it cannot not be about you. It is about mutuality: meeting in the common space of mutual interest. The moment the interest is no longer mutual, the date switches from being a place of joy to a place of awkward painfulness.

At the end of 40 days of prayer, Moses received the 10 commandments, and Jesus saw Satan. Lenten prayer opens our eyes to the deeper realities around us, the spiritual underpinnings of the things we take for granted. Prayer trains and develops the eyes of faith. This is because when we come into tune with the heart of God, we look along with God rather than looking askance. The rectifying of vision requires as its presupposition the rectifying of the heart. This is why prayer and fasting run hand in hand: because there is no straightening of what was bent without sacrifice