Over the course of each week during Lent, Dr. Junius Johnson will bring us weekly reflections and guide us in discovering the practices and principles that amount to lifelong discipleship.

“When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field right up to its edge, neither shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest. And you shall not strip your vineyard bare, neither shall you gather the fallen grapes of your vineyard. You shall leave them for the poor and for the sojourner: I am the Lord your God.” (Leviticus 19:9-10)

Almsgiving is an important but often overlooked aspect of Lent. But it is absolutely crucial: Apart from almsgiving, our efforts to de-center ourselves and reorient our focus to the divine are incomplete, for the love of God cannot be divorced from love of neighbor.

I don’t like this truth. As a recovering radical individualist and inveterate narcissist, the phrase “no man is an island” always rang like a challenge in my ears. But after years of kicking against the goads and striving to be sufficient to myself, the simple truth that God created us for community, ever witnessed to by the aching loneliness in my heart, at last broke down my defenses and stormed the city of my soul. Consider the juxtaposition of but two verses: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 22:37-40). “Whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point has become guilty of all of it” (James 2:10). If I love the Lord my God in the way described here but fail to love my neighbor as myself, I fail in one point of the law and become guilty of all of it.

I show that my love of God does not really encompass all of me, for it is not big enough to also love the ones he loves.

Truly, how could we love him well without loving the people he loves? And, what is more, we are called to love him in community with other co-lovers, and this shared love makes them dear to us. Love of neighbor is not an accessory command or extra credit for the especially religious: It is an integral part of the love of God, and a natural outflow from it, and its necessary completion.

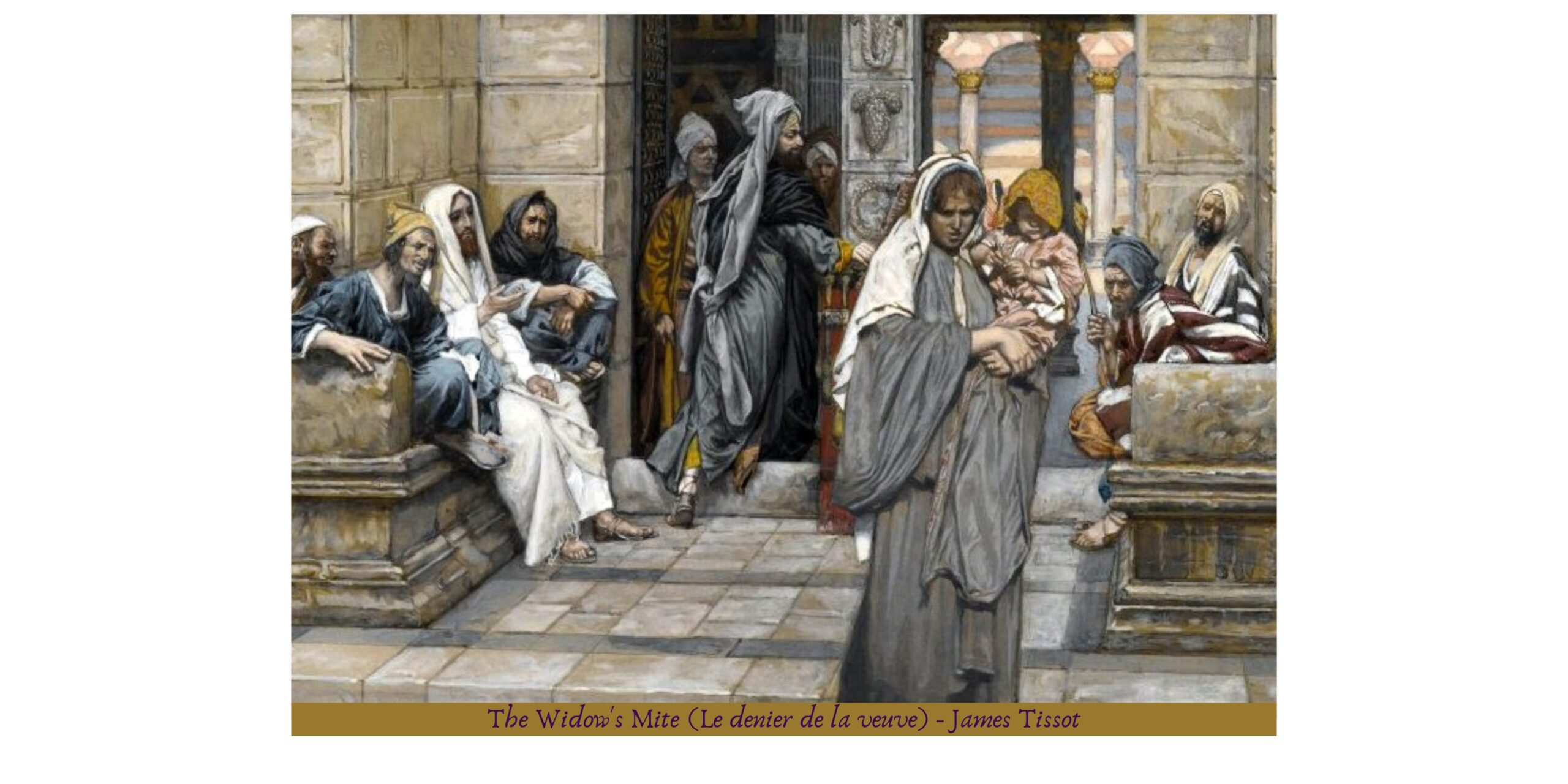

And so we should be solicitous for the well-being of both our Christian and non-Christian neighbors during this Lenten season. Traditionally, the money saved by fasting would be devoted to the hungry, which gives to fasting an active (practical) as well as a contemplative role. How much more purely the mind is devoted to God in prayer when fasting when we are able to recall that others are eating because we are not? What clearer way to love our neighbors as ourselves than by putting into their mouths the food we had prepared for our own?

This is what is so powerful about the Leviticus passage: You have labored hard over your field, tilling the ground, planting the seed, struggling against the never-ending waves of the invading army of weeds, and harvesting in haste and threshing in toil. Its fruits are the rewards of your labor, and you have prepared them against the harshness of the coming winter, and to keep your family fed and healthy.

But the Lord says: “Don’t reap to the edge,” which is as much as to say: “Don’t sew up your finances so tightly that nothing can escape for the poor.”

This cuts against the spiritual sophism of not giving to those who ask us for fear of how they will misuse it. Trying to ensure that no dollar of ours goes astray is like reaping the field right up to its edge. No, we should have fuzzy borders to our finances, places where the poor and the stranger can get in and take hold of what they need to live. “Give to everyone who asks you” (Luke 6:30). He doesn’t add: “Just be sure he’s not going to use it for something sinful.”

I am often put in mind of a story Doug Gresham tells of C.S. Lewis: While walking with a friend, a beggar asked for money. Lewis gave him the entire contents of his wallet. “You shouldn’t have done that, Jack,” the friend said. “He’ll only spend it all on drink.” Lewis is said to have responded: “Well, that’s what I was going to do.” I spend my money on frivolities and luxuries, things designed to dull the pain of worldly existence. I even spend my money in sinful ways. Why then should I feel I am doing something holy in withholding it from someone on the pretense that they might do the same? I do the other no spiritual good when I refuse him; but when I stop and give to him, I say to him: “I see you. God sees you. Take heart.”

Jesus said that what was done for the least among humanity was done for him. In almsgiving, we depart from the prison of self-love into the love of neighbor, and in so doing, through our neighbor we arrive at love of God by another route. And that love is enriched for having passed through our neighbor. This does not replace acts directed at loving God directly: you still have prayer and fasting. But it completes this love, and in it our conformity to Christ is made whole, for Christ was ever with the poor and outcast.