Content taken from chapter 2 of Reading for the Love of God by Jessica Hooten Wilson, ©2023. Used by permission of Brazos Press.

In De Doctrina Christiana (AD 426) Augustine advises readers to learn from human institutions—branches of knowledge—that will aid them in reading Scripture: “This whole area of human institutions which contribute to the necessities of learning should in no way be avoided by the Christian; indeed, within reason, they should be studied and committed to memory.” Augustine encourages readers to study not only the mechanical art of reading but also the arts of logic and rhetoric, as well as history, topography, zoology, astronomy, and even the meaning behind numbers and symbols. If we are to read the Bible well, Augustine suggests we try to become amateurs—lovers in the highest sense of that word—of all other human areas of knowledge.

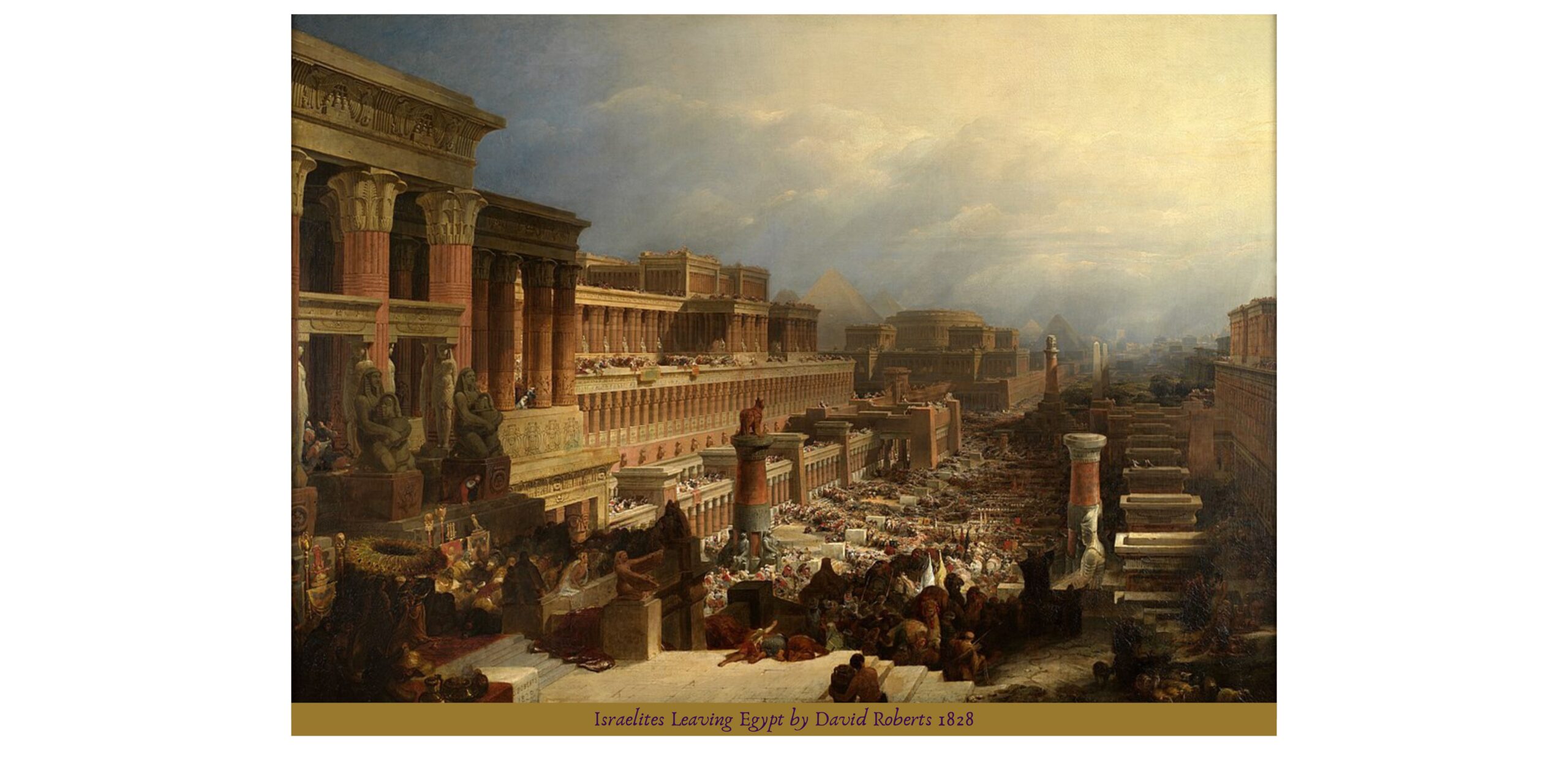

“A person who is a good and a true Christian,” Augustine writes, “should realize that truth belongs to his Lord, wherever it is found, gathering and acknowledging it even in pagan literature.” His famous allegory on how to glean truth from pagan literature is extracted from the book of Exodus. While Augustine refers specifically to the Platonists in this passage, we can broaden the application of his analogy to include all non-Christian writers:

Like the treasures of the ancient Egyptians, who possessed not only idols and heavy burdens, which the people of Israel hated and shunned but also vessels and ornaments of silver and gold, and clothes, which on leaving Egypt the people of Israel, in order to make better use of them, surreptitiously claimed for themselves (they did this not on their own authority but at God’s command, and the Egyptians in their ignorance actually gave them the things of which they had made poor use) [Exod. 3:21–2; 12:35–6]—similarly all the branches of pagan learning contain not only false superstitious fantasies and burdensome studies that involve unnecessary effort, which each one of us must loathe and avoid as under Christ’s guidance we abandon the company of pagans, but also studies for liberated minds which are more appropriate to the service of the truth, and some very useful moral instruction, as well as the various truths about monotheism to be found in their writers.

Augustine compares reading pagan writers to the Israelites carrying gold out of Egypt. Although the Egyptians employed the gold to fashion idols, God did not deem the gold itself impure but commanded the Israelites to cart it out of Egypt and subject it to their own uses. In the same manner that the Israelites discovered goods—namely, gold—among the Egyptians, Augustine claims that we may find truths within pagan literature. We must sift through the superstitions to claim the moral goods.

Traveling Supplies for Eternity

A contemporary of Augustine, Basil the Great, suffered under a similar protest from his fourth-century monks that we twenty-first-century teachers endure: students who cannot understand why we would waste our time reading anything outside the Bible. Apparently, this is not a new problem. In an address to these young readers, Basil begins by agreeing with his students that the Bible is the most important text to read, for we are destined for eternal life: “Whatever, therefore, contributes to that life, we say must be loved and pursued with all our strength; but what does not conduce to that must be passed over as of no account.”

The Bible acts as the standard by which all other reading is measured. As immortal creatures, we should judge books outside of the Bible by whether they foster sanctification and increase our knowledge of holy things.

However, we also must admit that the Holy Scriptures are difficult to understand. Perhaps, then, we consider outside reading as preparatory for reading the Bible. With Goodnight Moon and Shel Silverstein, for example, we learn how to read mechanically. Then, with Phillis Wheatley and Jane Eyre, for instance, we learn how to read poetic tropes, figures of speech, narrative strategies. We practice how to read well and increase our ability to read so that we can know the Scriptures better. Basil compares our task to that of dyers who “first prepare by certain treatments whatever material is to receive the dye, and then apply the color. . . . So we also in the same manner must first, if the glory of the good is to abide with us indelible for all time, be instructed by these outside means, and then we shall understand sacred and mystical teachings.” We begin the journey to reading the Bible well by first learning how to read and how to think at all. Then we learn history, science, rhetoric, languages, and so on. These liberal arts provide additional tools by which we can decipher meaning in the Scriptures. After this kind of liberal education, we may, “like those who have become accustomed to seeing the reflection of the sun in water,” Basil suggests, “direct our eyes to the light itself.” Like lifting lighter weights before the heaviest ones or like climbing the less steep section of the mountain before attaining the summit, reading human literature prepares us to encounter the divine Scriptures.

Once we are able to delight in the mystery of the Word, we do not forgo other literature, but we look within nonsacred books for what Basil calls “travel-supplies” for eternity. As bees who flit from flower to flower to possess the honey while ignoring the thorns, Basil writes, so readers should be drawn to the passages in which writers “have praised virtue or condemned vice.” Basil names Homer and Plato as examples of those writers of eternal goods. From Basil’s perspective, Homer uplifts heroes for being heroic, and Plato rightly castigates the sophists. Thus, we can glean from these truth-sayers goods for our eternal journey. With a spirit of inquiry, we should follow Basil’s example and ask, What in this book praises virtue as the Bible defines virtue? In a similar spirit to Scripture, what condemns vice? Since the time of Basil, there have been many writers who have shown us what it means to live a good life in accordance with the Word of God. For me, I have learned about forgiveness from The Brothers Karamazov. I have learned about freedom of conscience from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, about dying well from Ernest Gaines, about loving what is beautiful from Sigrid Undset. For the adventure of eternity, Basil exhorts us “to acquire travel-supplies, leaving no stone unturned, as the proverb has it, wherever any benefit towards that end is likely to accrue to you.” Or, as St. Paul writes in Philippians 4:8, whatever is true, noble, admirable, think on these things.